“If I died,” my mother used to say, “your father would be terribly sad. But he would not die. Without music, though, he wouldn’t last a week.”

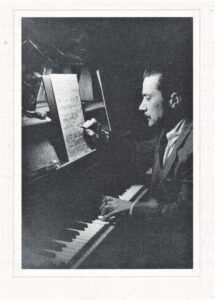

She was right. My father supported us with his violin, which meant cobbling together an onerous schedule of orchestra jobs, chamber music performances, teaching, and whatever else came his way. Whenever he had a free half hour, he would rush to the piano and compose. It was a hard life, but he never dreamed of doing anything else.

My mother loved him and his music. But she thought that he could get wider acclaim and have an easier life if only he would put himself forward more, schmooze the society ladies on the orchestra board, be a little pushy. But my father wasn’t interested. He was willing to work his fingers to the bone—even put up with another performance of Carmen (which he deplored) or Tchaikovsky (ditto)—as long as it had to do with music. Everything else simply bored him.

The entire family was in awe of my father’s dedication. My mother’s admiration, however, was tinged with envy—she was clear-eyed enough to know that, as hard as my father worked, he was also, for the most part, having a wonderful time. She, on the other hand….

I, a female child, imbibed this dynamic. Although my father never made speeches about his love of music, I knew in my bones that he was happier than my mother, who depended for her happiness on our affection and our need for her. From an early age, I intuited that the means to happiness were within his control, but not within hers. I wanted to be like him, but felt fated by my gender to be like her.

As an adult, I used to regret that a passion for one thing—twelve-tone music, the life-cycle of the blood fluke, semiotics—had not grabbed me by the throat and shoved me down a clearly marked path. Instead, I did a lot of wildly different things, many of which I enjoyed. However, having inherited more than a little of my mother’s drive, I was enslaved by the notion that whatever I did had to have merit and validation beyond itself. At school, I needed good grades. At work, I needed promotions. My back-to-the-land fantasies had to pay for themselves. My writing and my art had to sell.

It is only now that I have begun to understand the value of my father’s example. True, he had that gift from the gods, a fierce vocation. But he had another talent that I am presently trying to emulate: the ability to become fully immersed in his work for its own sake, without concerning himself with ultimate goals or external success. He was, most of the time, in an enviable state of flow.

At last I have reached the age when making “good grades” is neither possible nor relevant. Life itself has forced me to let go of long-range plans and ultimate goals. Now, when I write or draw I try to be more like my father—and I even harbor a secret ambition to become like those Zen monks who spend days making elaborate sand mandalas and then sweep them up and throw them in the river.

To date, I can report some modest progress. I no longer torment myself by questioning the final relevance of the things I spend my time doing. But am I in flow when I write? Well…if by flow you mean a state of intense absorption in which one tends to lose track of time and show up late for lunch appointments, then yes, I often am. But the word “flow” also connotes a sensation of pleasant ease, like a river meandering peacefully to the sea, and that is certainly not what I feel when I write.

Writing for me feels more like wearing a wool undershirt—scratchy and uncomfortable, and delightful when I can finally peel it off and feel the cool air on my skin. But I find that if I’m willing to stay with the discomfort, just kind of breathe and make friends with it, things often come together. And for a blessed moment I am that river, making its tranquil way to the sea.

12 Responses

Beautiful! I’m happy that you have decided to share your beautiful writing with your friends!

It’s friends like you that keep me writing, Dot.

Lali, you are an inspiration to so many of us who. Please keep flowing.

I can only try!

Send this one to the New Yorker.

Ooops…too late! The New Yorker only takes stuff that’s never been published before–even on the web (and that’s not the only reason this piece wouldn’t get in, alas).

This is beautiful, Lali! Your words always make me smile. And I especially loved this wee snippet – “even put up with another performance of Carmen (which he deplored) or Tchaikovsky (ditto)”

How lucky your father was, in so many ways. From another Jack of all trades.

It’s time that we Jacks of all trades got some well-deserved recognition, don’t you think?

I still have that drive. I tried pouring it into other things before becoming a novelist, but those things came to untimely ends.

The drive is still there, the flow, sometimes. But the passion doesn’t leave.

I have one more book (at least) to finish – and then I may take a break.

This trilogy has been my mistress for over twenty years – it will hold to the end if I do.

Twenty years! May the passion last you another twenty.

I’m another one who has a long history of skipping from interest to interest, often wishing I had a field. A focus. Although I can’t say I’m sorry the life cycle of the blood fluke never grabbed me by the throat.

Happy to read your writing again, Lali. For a long time I haven’t kept up with my friends’ blogs. Or my own writing. Or housekeeping. I blame the pandemic. It might as well be good for something.

Good to hear from you, Susan! I hope you are doing well. I know what you mean about the pandemic–it has affected all of us in many strange ways, even if we’ve been spared by the virus.