There are no photos of my parents’ wedding. Somebody did make a home movie of the occasion, but since we didn’t own a film projector, I never saw it. But I have my own vivid movie of that day, made up of the stories that my mother used to tell.

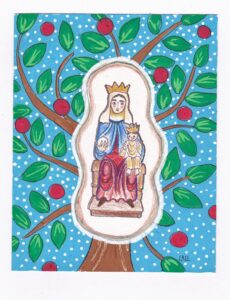

They got married in a hermitage in the countryside, just outside the Catalan village where my mother’s parents had a farm. The little church was dedicated to Nostra Senyora de l’Horta, Our Lady of the Orchards, whose miraculous statue had been found by a shepherd in the branches of an oak tree many centuries ago.

As my parents, having said their vows, knelt before the priest to receive the final blessing, the altar boy tripped on my mother’s veil with his hobnailed boots. “I felt this tremendous yank and heard a tearing sound,” my mother used to say. “I turned around, and there was my veil, with a huge hole in the middle.”

Growing up, the story of the torn veil became associated in my mind with other magical characteristics of the hermitage. I was too young to know about the early Greeks’ veneration of sacred spaces in nature—a tree or a spring inhabited by a local nymph in charge of protecting the area and ensuring its fertility. But I sensed the mystery of the tiny chapel, silent and empty except on special occasions, surrounded by trees and gardens and, at its heart, the statue of Our Lady.

This was not one of your graceful, smiling madonnas, but a reproduction of a Romanesque original that had been burned by anarchist militias during the Spanish Civil War. She sat rigid and staring, the globe of the earth in her right hand, her left grasping the shoulder of her equally rigid Child. There was nothing cuddly about Our Lady of the Orchards, but she radiated power. In times of drought, the villagers would take her out and process with her through the fields, chanting “Give us rain, since you have the power.”

I wonder if the friends and relatives gathered in the chapel reflected on the symbolism of the tearing of the veil, but I can’t help thinking that the Madonna, in charge of the fertility of the faithful as well as of the orchards, had something to do with it.

After the wedding, everyone made their way in the ripe September sun back to the farm, where they sat in the cool, tiled dining room and drank champagne and ate the last of the summer melons. Then my father’s parents, his two sisters, his widowed sister-in-law, and the newlyweds climbed into the van that was waiting to take them back to Barcelona. In addition to my mother’s clothes and books, and a basket filled with eggs, raisins, and sausages from last year’s pig, they loaded a double-bed mattress on the roof of the van and secured it with ropes.

They arrived in Barcelona well after dark, and drove to the fifth-floor walkup where my parents would begin their life together. Who got that mattress up to the fifth floor, and how? It must have been my grandfather and my father, still in their wedding finery. Struggling and sweating up those narrow stairs (the same stairs down which my pregnant mother would tumble six months later), stopping at each floor to flip the timer to light the next flight, they carried the mattress upon which I would shortly be conceived.

Once the men had dropped the mattress on the majestic mahogany bed, did the women help my mother to unfold the lavender-scented sheets with her embroidered initials, and make the bed? Did they open a final bottle of champagne and drink it out of the brand-new crystal goblets?

I know from their letters that my mother was the first woman that my father ever kissed, so what awaited them that night was not trivial. How did the family finally take their leave? I imagine that they all kissed each other resoundingly on both cheeks; my father kissed his parents’ hands; they made the sign of the cross over him; and then my grandparents and my aunts turned away, waving and saying adéu, adéu as they headed down the stairs, and my father closed the door.

A quarter-century later, as my fiancé and I were planning the honeymoon that his parents had given us as a gift, my father suggested that we might want to wait until we’d been married a while before taking the trip. “You see, when one is first married,” he explained, “everything is so new and so different that one doesn’t really need to be in an exotic place….”

9 Responses

Your story makes me think of our (Kathleen and my) wedding night. Our families were left behind while we drove to a hotel in Atlanta, facing life alone, but together.

And you’re still facing life, together. Love to you both.

I love your father’s final comment about waiting for the honeymoon.

It’s one of the last memories I have of him. He died of lung cancer six months later.

Me too. A great line that put a smile on my face that’s still there!

Thanks for reading, Joan!

Our first apartment was a fifth floor walk up in NY city. 11 months later a big, heavy, baby boy arrived and we had to carry him and a stroller up all those stairs! And any groceries. And anything else! Finally, when I finished my 5 year nursing program at Cornell Nursing school, we moved to a house in NJ and had our first good night’s sleep in months. He was now in his own room! And NO five flights of stairs to carry him up.

You must have been in amazing physical shape, despite the lack of sleep!

There is nothing wrong with starting even with your spouse – and much to be gained from not having to deal with bad habits, including lack of communication.