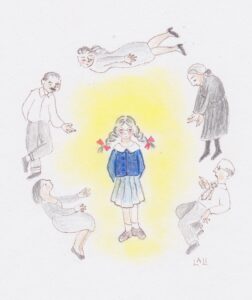

The children who, like me, were born shortly after the end of the Spanish Civil War, embodied the hope for a life free from the horrors of the recent past. I wrote here about how my birth was one of the first things that my family had to rejoice about. My first smile, first word, first step were, for the adults who orbited my crib, markers along a path of recovery from the years of fear and deprivation that preceded my arrival.

For most of those postwar babies, their status as revered icons and harbingers of a brighter future shifted as new brothers and sisters arrived. For me, that did not happen.* From infancy through puberty, I was the only child on both sides of the family, the star of the show. Not that my performance always elicited applause. That mantra of 21st century parenting, “good job!” was unknown to my family. What my behavior did elicit, invariably, was attention. Nothing that I did went unremarked. If I said something witty, people laughed. If I seemed quiet, they asked what I was thinking. If I caught the slightest cold, they hovered with aspirins and thermometers. But if I deviated for a moment from the ideal of a patient, polite, compliant girl child, they let me know in no uncertain terms.

The most attentive member of my entourage was, of course, my mother. It may be that the times and the culture conspired to confine a woman bursting with life force and intelligence to the duties of wife to an undemanding husband and mother to a single child. Whatever the reason, her focus on me was unswerving. Despite the family doctor’s advice—“don’t watch the child so closely!”—she was intensely concerned about my health. I reached puberty before I was allowed to decide for myself whether to wear a sweater. And I still remember one morning, as I drove off to college, my mother running alongside the car, holding out a hardboiled egg, “Eat this,” she commanded, “or you’ll faint!”

My behavior was also a concern. Pouting was not allowed—after all, what was there for me to complain about, compared to what everyone had suffered during the war? She expected me to go about my duties as cheerfully as Pollyanna. Above all, she wanted me to be happy, an expectation that I soon made a point of disappointing.

She made up bedtime prayers for me, the most ardent of which consisted of asking God to send me a little brother or sister. How I longed for that imaginary sibling! Someone to play with, to allay the boredom of endless hours spent sitting in concert halls or visiting ancient black-clad relatives. I needed another child—or better, half a dozen of them—to distract my mother from her passionate focus on me. I needed someone my own size with whom to learn to compete and squabble and reconcile.

How sorely lacking I was in these skills became apparent when I entered first grade, having hardly ever been in the presence of another child. Suddenly there I was, no longer the center of the universe, unpracticed in the arts of getting along with, and holding my own among, kids my age. The shock was appalling. I felt like some defenseless explorer lost amid savages, shrill, unpredictable creatures sorely lacking in the deference and attentiveness that I was accustomed to getting from adults. Not only did my classmates ignore me, some of them actively disliked me. I found them incomprehensible, and far more alarming than even the German nuns who taught us.

Recess was the worst. I had no idea how to join in games or approach the other girls. After a couple of years of exclusion and embarrassment, one day I took the bull by the horns and asked a popular girl if she would be my friend. “No,” she replied, and turned away, her braids swinging. There was one girl who tolerated me, but she was so low in the pecking order (despite my naivete I was well aware of the pecking order) that I preferred to endure recess alone, praying that class would resume soon.

But it wasn’t all bad. Realizing that if I stayed quietly in my room I could avoid my mother’s scrutiny, I came to enjoy being alone. And there were advantages to growing up being listened to by grownups. I had no trouble speaking up in class. As a foreign student in Ecuador and then in Alabama, I was often invited by the teacher to talk about my experiences. Standing in front of the class while my peers had to sit still and listen, I was happy to oblige. In eleventh grade, my English still shaky, I got third prize in a statewide speech contest: in front of an audience, I was in my element.

This went on for the rest of my career. Oral exams, job interviews, speeches to the many or the few simply evoked a pleasant tingle of excitement, the closest I ever came to a fear of public speaking. But to this day, invite me to a party where I am expected to circulate, introduce myself, and make conversation with strangers, and the old agonies resurface. And once more there I am, in round glasses and fat braids, standing at the edge of the playground, my brightness dimmed and no satellites in sight, wondering how soon I can escape to the comforts of my solitude.

*(Technically, I am not an only child. My sister was born when I was sixteen, so for all practical purposes we are both only children.)