In my earliest memories, I am the center of a planetary system, a small but potent sun orbited by much larger satellites—parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. I got off to a wobbly start, however, howling around the clock for the first month of my life, until my veterinarian grandfather came to Barcelona. He picked me up from my lace-enshrouded bassinet and, being familiar with the look and feel of healthy newborns of various species, declared “This child is starving to death.”

There followed a fruitless search for infant formula. All food, let alone formula, was so scarce that, in the five years following the end of the Spanish Civil War, 200,000 people died of malnutrition. Fortunately, a friend of my father knew someone who owned a powdered milk factory, and was willing to supply the precious stuff. It took two of my satellites, my mother and her sister, to feed me the slurry of milk and bread. One would put a spoonful in my mouth while the other filled the next spoon. If the flow was interrupted for even a second I would fly into a rage and vomit the whole.

The malnutrition episode made a deep impression on my mother and the women of the family, whose mission became to make sure that I didn’t die of starvation. Second only to food on the minds of the satellites was keeping me safe. “Don’t run, you’ll fall!” they said. “Don’t stay out in the sun, you’ll get heat stroke! Don’t stand in a draft, you’ll catch cold! Don’t read after meals, you’ll get indigestion!”

This became annoying when I got older—at age twelve, I resented it that my mother still sent the maid to walk me across the road to wait for the school bus. But in infancy, that circle of loving, attentive faces ever bent towards me felt like my due, and I generously shone my light upon them all.

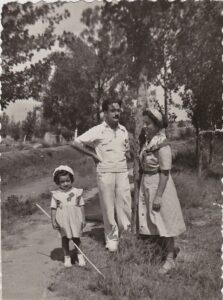

I can imagine what it must have been like for my parents and grandparents, after three years of fear and anguish, to have new life in their midst, the first of a generation with a future where, God willing, bad things wouldn’t happen anymore. Is it any wonder that conversations about the war, if any, only took place out of my hearing? “Allegries,” (joys) my mother used to call me, and she and the whole family drank in my baby merriment like rain after a drought. Through no effort on my part, I was helping them to get over the war.

They were happy to see me happy, but with that came the at first unspoken obligation for me to be happy at all times. After all, what was there for me to complain about? That became a problem when I reached puberty. “Don’t make such a big deal of it,” my mother would say when I kvetched about acne or a too-strict curfew. “When your father was just a little older than you he couldn’t leave the house at all.” Predictably, those admonitions only made me insist all the more on the awfulness of my troubles, and I adopted a melancholy stance out of sheer contrariness.

As for my father, he never alluded to the war in my presence, and I, in my narcissism, neglected to ask what it had been like for him. Did you miss your friends? I could have asked. Did you fight with your sisters? How did you divide up the food? What was it like not to be able to play the violin?

So the silence continued, but what it hid spread its wings over me nevertheless. My father’s sufferings, his mother’s sorrow about her firstborn’s death, my maternal grandmother’s anxiety about impending doom did not leave me unscathed. Although they didn’t talk about these feelings and experiences, I sensed them and, albeit indirectly, replayed certain aspects in my own life. It is not by chance that for most of my adult years I was obsessed with self-sufficiency, and grew vegetables and kept chickens and goats in an unconscious attempt to ward off famine. And it is not entirely by chance that the near seclusion forced on me by thirty years of chronic fatigue syndrome partly echoes (minus the hunger and the terror) the experience of my father’s war.

10 Responses

Way too much to put on the shoulders of one tiny girl – similar to the Chinese experience with the one-child policy (except that girls were often not allowed to be that one child) – the little emperors and empresses were both the salvation of their families, and required to be perfect at all times. You’d find some companions there.

My mother had your other experience – she was a tiny baby when my grandparents moved back to Mexico City from Illinois – and my mother, their firstborn, was what they now call ‘failing to thrive’. I don’t know how they fixed the problem, but it was probably my grandmother’s failure to provide enough milk (I don’t remember Mother ever giving me that particular datum), but it couldn’t have helped to move to a strange country for her, with a very traditional Mexican MIL, with a 3-month old.

Glad you made it; sorry your parents’ first child didn’t.

It was my grandparents’ first child who died–but at age 30, partly as a result of lack of medical care during the war.

The pressure to be happy is also felt, I am told, by children of Holocaust survivors.

So many deaths this and the previous century. Only now it is possible to prevent many of them – and the greedy politicians won’t make the necessary appropriations and public health efforts.

It goes on daily, from war and poverty, but mostly because the countries can’t manage their budgets for their citizens’ benefit, and instead have all that nice money going to the cronies of their ‘leaders.’

Turns my stomach.

The 20th century was so horrific, and this one isn’t shaping up to be much better.

brilliant as usual. I was also the blessing during war when all the men were away and the women were on the farm. After two years, my father came back and we three ventured out into the towns. My mother recalled getting off the train excitedly seeing her family approaching her, then running right past her to embrace me. I was trailing a bit behind on a leash.

A blessing on a leash! 🙂

Such a poignant perspective, Lali.

Thanks for reading, Mary.

I recently bought The Body Keeps the Score, a book about how trauma in early life manifests later. Trauma comes in many forms. I live with CFS too. You know, of course, that your “narcissism” was simply how we are in childhood–and often quite a few years beyond. I sometimes think of how hard it must have been for my dad to lose his sister and watch his mother disappear into dementia. I learned at age 9 that asking about my mother’s death made him cry, so even when I was a mother myself I never brought up other tragedies. Now, of course, I wish I’d at least offered some words of empathy. You’re such a good writer, Lali.

Susan, I had no idea that you have CFS. I hope that you are able to manage it as well as possible. Losing your mother so young and witnessing your father’s sorrow must have been terribly difficult for you.