“You’re going to the opera again?” I would whine as my mother stepped into her evening gown. I was a clingy kid, and hated being left alone with the maid when my mother went out at night. Once a week during winter and spring she would go to the Barcelona opera house. My father played in the orchestra, and as the touring opera and ballet companies came through the city, he would get tickets for her.

She wore a long fitted black satiny dress with a v-neck and a slit at the back of the skirt so she could walk. The sleeves went down to the elbow, befitting a Catholic wife and mother. The first time I saw her in the dress, amazed at its beauty and elegance, I said something about how décolleté it was. Suddenly she became very serious, looked me in the eye, and said, emphasizing every syllable, “I would never, ever wear anything immodest.”

Next she would do her make-up, applying little upward strokes of eyeliner to the outer corner of her eyes, like arrows pointing to her brain. Then it was time to do her “bun.” This was a hank of human hair—I always wondered from whose head it had come—which she would comb carefully, mold into an s-shape, and secure with hairpins to the back of her head. She would fasten her pearl necklace, step into her shoes and, twisting backwards, check, one leg at a time, that the seams of her stockings were straight. I grew up watching women make that now-vanished gesture, which for me embodied the very essence of femininity.

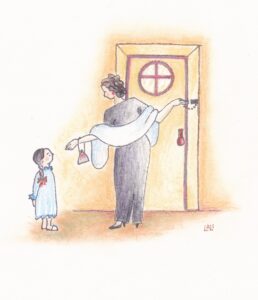

Then came the final touch: the stole. For their anniversary my father had given her not one, but two fur stoles. One was white and one brown, and I was allowed to feel them if my hands were very clean. The two stoles seemed to me, and to the entire family, an extravagance worthy of a sultan, but because everybody thought that my father was a saint, they abstained from criticism.

Having chosen a stole, she would kiss and make the sign of the cross over me, and go off into the night. She always went alone. On opera nights my father didn’t have time to come home for dinner, so she would meet him at the opera house and they would walk home together after the performance. The next day, they would comment on the performances, my father going on about the wonders of the guest conductors and the singers—Maria Callas, whom he did not adore, and Renata Tebaldi, whom he did, among others whose names I have forgotten. And my mother would exclaim about the plumpness of the Wagnerian singers, so that in the love scenes in Tristan und Isolde the tenor and the soprano, too fat to embrace, had to settle for grasping each other’s fingertips.

When a touring American company performed Porgy and Bess, my parents talked for days about the music by the great Gershwin, the fantastic voices, the superb acting, and the fact that the entire cast was Black. (Other than the occasional sailor wandering the streets near the harbor when a U.S. navy ship docked in Barcelona, persons of African descent were a rare sight at the time.)

My mother would save the ballet programs for me. There were full-page photos of amazing ballerinas like Maria Tallchief (a real Native American!) in those tiny tutus that looked silly on grown-up ladies. They too, I noticed, wore those little upstrokes at the corner of their eyes. And I wondered at the male dancers in tights, who all seemed to suffer a strange malformation in the area below the belt. From the hints my mother gave, some of those ballets must have been pretty racy. In certain scenes in Scheherazade, she, as a good Catholic wife and mother, had to avert her eyes from the dancers’ undulations.

When the 1954 season ended, we left for Ecuador. The black dress, the stoles, and the bun remained behind. I never saw my mother wear them again. But they are preserved in the storage trunk of my memory, where I sometimes take them out, and run my fingers over them.

12 Responses

How lovely! And how sad that she lost these precious things when you moved.

Wonderful being present in person for Maria Tallchief.

I laughed at the ‘malformations’ – so perfect a description from a girl-child.

Everything is so visual I might have been there.

Love to hear these words, Alicia, especially coming from a writer!

Sigh. I love this. What an incredible time and place to be alive!

Yes, the 18th century was pretty exotic, in retrospect….

Beautiful descriptions of your Mother and of your memory truck

Every time I open that trunk I expect to find it empty, but I usually find something in there. Thanks for reading, Sally.

I loved this too. It was about Barcelona, but it could have taken place in New York. I saw Maria Tallchief dance when I was a child, and after I was married we lived in the same building as Renata Tebaldi. I worked at Lincoln Center, and your father’s opinions of Tebaldi and Callas were shared by many. Thank you for letting us have a peek into your memory trunk.

You lived in the same building as Renata Tebaldi??? Also, how amazing to have that Callas/Tebaldi memory, consisting of bits of overheard adult conversations, validated after all these years.

I still remember my maternal grandmother’s fur stole–fox? mink?–and the animal’s mouth that gripped the tail as though it were alive–About six pr seven, I was discretely and silently fascinated. I think I may have touched it as if to make sure “it” was actually dead–even though I deep down knew it was. Although my step-mother was a very difficult woman, I think even then–without really thinking about it–approved of her never wearing fur.

I remember those too, and how spooky they were! I think that on some the jaws actually hinged so the wearer wouldn’t have to remove her hat or mess up her hair when taking off the stole.

Your discussion with Blair makes me think of the Ouroboros. In light of that, makes me wonder about the symbolism behind those stoles. What did the creators have in mind? Was it the Ouroboros.

Thank you for giving me the name of the serpent/dragon eating its tail (I had to look it up). I think those stole makers were more into selling furs than contemplating symbols of infinity.