In 1959, my parents and I went back to Spain for the summer. This was a big deal. Since leaving Barcelona, we had spent three years in the wilds of Ecuador and one year in the wilds of Alabama, and I had evolved from pigtails and scabbed knees to full-blown pubertal brouhaha. I couldn’t wait to see my grandparents, aunts, and uncles again, and to impress them with my made-in-America maturity and sophistication. It was crucial that I take the right equipment with me, so in addition to summer dresses and a bathing suit, I packed my bag of jumbo hair rollers, my tube of Clearasil…and my apron.

This was not your jolly French maid kind of apron, but a sober, over-the-head, shoulder-to-hip affair in a matronly floral print, with a big kangaroo-style pocket over the belly. Why would a fourteen-year old girl even own such an article, let alone choose to carry it across the Atlantic on vacation? The reasons were various and silly, but potent.

Our year in Alabama was the first time in our family’s history when we did not have a live-in maid. (Mind you, this was not a reflection of wealth, but rather of the poverty of the underclasses in Spain and Ecuador.) My mother had enlisted me as assistant housewife and presented me with the apron, and I plunged into my new role with enthusiasm. Setting and clearing the table became my job (including, at my mother’s insistence, putting a flower or at least a few green leaves in a vase at the center), as did washing the dishes. From there I graduated to dusting, sweeping, and ironing.

I embraced my chores not because I enjoyed them but because I mistakenly assumed an implicit exchange of favors with my mother: if I accomplished these grown-up, womanly tasks, she would allow me grown-up, womanly privileges. If I proved a whiz at ironing shirts (start with the back, follow with the sleeves and the front, end with the cuffs and collar and hang immediately, before it wrinkles again) then surely I would be allowed to go to a dance, perhaps wearing the slightest hint of Tangee on my lips. (It took me a long time to realize that my budding domesticity did not alter my childish status in my mother’s eyes.)

But there was more to the apron than that. An apron, in those days, was not just a clothing protector. It was the ultimate signifier of domesticity and femininity, an outer garment that proclaimed, along with the hidden bra and garter belt: I am a Woman, and I delight in Womanly things. The garter belt and stockings were forbidden by my mother (the bra had been a necessity since age twelve), but if anybody had any doubts that I was a Woman in looks and inclination, here was the apron to prove it.

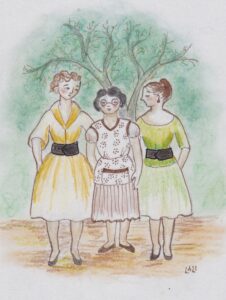

So I took the apron to Spain. In the single extant photo from that trip I am standing under a tree with my fashionable aunties, they in full skirts and four-inch-wide, cinched leather belts, and me in my apron, looking like their mother. They never said what they thought of the apron but, taking me in hand, they sewed me a sleeveless, full-skirted dress and bought me one of those belts.

My love affair with the apron faded quickly, as did my fondness for domestic chores, which grew exponentially when, a year later, back in Alabama, my sister was born and I was handed the additional jobs of washing and sterilizing formula bottles and hanging diapers out to dry. Plus, the times they were a-changing. The 60s saw the demise of garter belts and stockings (replaced by panty hose), full-body slips (replaced by nothing), and aprons. For one thing, aprons looked ridiculous on top of miniskirts. For another, our ideas of what made a woman interesting and desirable were shifting: one of the most popular cookbooks of the decade was The I Hate To Cook Book.

It took Martha Stewart to resurrect the cult of the domestic goddess, but even then the apron didn’t make a comeback, possibly because of the plethora of new stain-removing products on the market. But, googling aprons while writing this, I see that the apron is now back, albeit in a no-nonsense, award-winning chef incarnation—and a glance at the advertisements shows that at least half of the apron-wearing models are male.

And that, as Martha would say, is a good thing.

4 Responses

I met you in “the wilds of Alabama.” I never thought of it in quite that way.

Bob is the one at our home who wears aprons frequently.

I hope he has some of those spiffy “serious” ones.

No apron stories to share, alas.

My mother sewed on for my husband, and I had a couple in the drawer. That’s it.

Now he uses one when we sit in our livingroom chairs to watch TV – to keep crumbs and spills off his clothes. Occasionally, he vacuums the rug where said crumbs tumble when he gets up.

If I were well, there would be other standards in my home. I’m not – so I get what I get. I ignore the rest, happy I’m not the one vacuuming!

Life never turns out quite like you expect it to.

I have a whole harvest of crumbs that have fallen inside the arms of my wicker reading chair, never again to see the light of day.