![]() The year I turned five I began to think of myself as being six. Being six meant starting school and having my First Communion, so six seemed a good thing to be. This habit continued through my childhood, when being a year older brought with it new privileges. Eventually, though, it faded, there being nothing inherently more exciting about being, say, twenty-nine as opposed to twenty-eight.

The year I turned five I began to think of myself as being six. Being six meant starting school and having my First Communion, so six seemed a good thing to be. This habit continued through my childhood, when being a year older brought with it new privileges. Eventually, though, it faded, there being nothing inherently more exciting about being, say, twenty-nine as opposed to twenty-eight.

Then in my late sixties I started once again thinking of myself as being a year older than I actually was. But now I was doing it for the opposite reason: feeling somewhat queasy about the accumulating years, I thought I might as well get used to the idea of being sixty-five, when I was really only sixty-four.

And that is why, having just turned seventy-nine, I think of myself as being eighty.

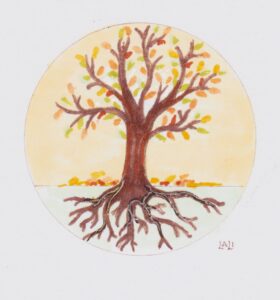

An October birthday is fertile ground for aging metaphors. Take the trees, for example—how fitting that both they and I are in shedding mode. They are letting go of leaves, and I of…well, you name it. Shedding hair and other charms is the most obvious parallel, but it’s the invisible sheddings that really get to me. Words, for one: what is the word that means “having to do with the end of the world”? (eschatology—I looked it up). I shed names, too, not just those of someone I just met, for which there is zero hope, but of people I once knew well and liked (what was the name of the best man at our wedding?). Disconcertingly, words and names I thought were gone for good sometimes come winging back when I least expect it, but seldom when I need them.

I shed facts, too, stuff I once knew as well as my own name: the difference between mitosis and meiosis, how oxygen gets into the blood, the year the Moors invaded Spain.

Just as trees don’t lose their leaves all at once, I too cling desperately to a smattering of unrelated names and data, mostly of things that I have no earthly use for: the three Fates (Clotho, Lachesis, Atropos), three rivers of the underworld (Lethe, Acheron, Styx). But who was the boatman who ferried the souls across? (Charon. I looked it up.) Funny how I do reasonably well in Greek mythology, but can no longer recite the Ten Commandments, the Seven Sins Against the Holy Ghost, or the Corporal Works of Mercy.

I try to keep in mind that, even when every last leaf is gone, in winter the tree is not dead but asleep, and perhaps dreaming, as it continues to serve as a perch for birds and a den for squirrels. And even as photosynthesis comes to a halt, the roots are anything but dormant. They are growing, searching for and retaining nutrients to keep the tree going until the spring. I too, as I enter the winter of my life, feel that while there is less of me on the outside, my roots inside are busy digging deeper, finding nourishment.

Now for the final part of this all-too-obvious botanical metaphor: trees die, and so will I. Sometimes they die in winter, literally exploding because the sap in them expands when it freezes and bursts the cell membranes. But they die at any time of year, from fungi and insect depredations and winds and fires and drought and floods. But when a tree dies and falls on the forest floor, it gives itself over entirely to providing shelter and food for millions of organisms, from mice to microbes, who in turn do their bit to keep the forest alive.

Despite all this, my least favorite yoga pose is “tree.” No matter how hard I try to “ground” my foot and focus my gaze and mind my breathing and stretch my arms/branches towards the sky, I inevitably waver, stagger, and lurch. Balance being another of the “leaves” that I shed a while ago, the pose makes me feel foolish, insecure, ungainly, and unsafe. But as I turn not-quite-eighty, I will continue to practice it in honor of the trees, who are at such enviable ease both in their standing and in their falling down.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2 Responses

Tree roots go wide to support the tree, ground it, tie it to Mother Earth.

All we have is little feet, but we make do.

We do what we can!