This was the only thing he ever said to me about those years: “We were all so hungry that at night, before going to bed, we would go to the kitchen and fill our stomachs with water so we could sleep.” I used to imagine the whole family—his parents, his two teenage sisters, his older brother with his Mexican wife and their two little boys, and Llúcia, the ancient maid who had been with them since childhood—lined up in the kitchen. I could hear the banging of the water in the pipes, smell its chlorine smell as it gushed into the marble sink. I could see them all, politely taking turns at the brass spigot, then making their way slowly to their dark bedrooms, the bad-tasting city water sloshing inside their distended stomachs.

Everything else I know about my father’s experience of the Spanish Civil War, which began in 1936, when he was 22, and ended in 1939, I heard from my mother, long after his death. She told me how, even worse than the perpetual hunger was the fact that he had to stay hidden in his parents’ Barcelona apartment the entire length of the war. He had belonged to a Catholic youth organization, which rendered him liable to being executed by leftist militia venting their rage against the middle class, the Catholic Church, and the world in general. (As in any civil war, equivalent horrors were being perpetrated against leftists by the other side.)

“Your father’s best friend from high school,” my mother said, “was dragged out from under the bed where he was hiding and loaded into a truck on the way to being shot. Luckily he was a clever and charming man, and somehow he managed to make friends with one of the guards, who let him jump out just in time.”

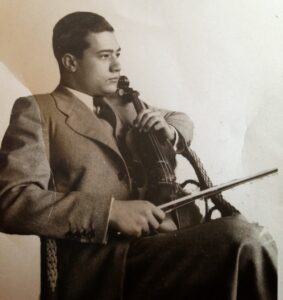

“Not only could your father never go outside, but he had to stay away from windows lest the neighbors see him and betray him to the militia. He couldn’t wear shoes, since his tread might give him away, or speak above a whisper. And he certainly couldn’t play the violin. Can you imagine your father unable to play for three whole years?”

“To keep busy and make a little money, he painted buttons. Large buttons made of vegetable ivory were fashionable then, so he painted tiny Japanese landscapes on them, and his mother sold them. Then his brother got sick,” she continued. “His marriage to a Mexican citizen had kept him safe from the militias, because Mexico was on the side of the Reds. But when he got lymphoma, there were no doctors to care for him, so he got weaker and weaker and died a couple of years after the war, when he was thirty.”

I try to imagine my young father, painting buttons in the dim light away from the window, while his brother dozes in the bedroom down the hall, the two little boys squabble, his teenage sisters complain they’re bored, and in the kitchen his mother and Llúcia are making soup with water, a few cloves of garlic, and the last bits of stale bread. At night, after the children are in bed, everyone assembles in the living room and my grandfather leads the rosary, ending with the litany of the Virgin: Morning star, Consoler of the afflicted, Queen of peace, pray for us….

Ten people in one apartment, cold in the winter and hot in the summer, hungry and terrified, for three whole years.

I remember my grandmother stroking my hair when I was little, sighing (she sighed a lot) and saying, “your father is a saint.” Was she referring, I wonder now, to his behavior during the war years? Did he really never complain? Did he always offer his portion of food to whoever seemed the hungriest? Did he never snap at his little nephews? I suppose that starvation must have put a damper on his physical vigor and his sex drive, but surely there must have been moments when he raged?

I will never know. I was born five years after Franco’s victory, and during my childhood nobody on either side of the family talked to me about the war. Why burden a small child with terrible stories? But I remember clearly hearing snippets of adult talk: “they killed her brother during the war…she was never the same again…they don’t know where he is buried….” And then my father’s voice, made raspy by the Turkish cigarettes he smoked non-stop: “we were so hungry that we filled our stomachs with water so we could sleep…”

(To be continued.)

3 Responses

Thank you for sharing even the though memories.

Thanks for reading, Alicia.

TOUGH. The TOUGH memories. Fingers!