#1–Quito, Ecuador, 1955. From one of our forays into the Amazon, we bring home a sloth. On those trips, we are often approached by locals wanting to sell us various kinds of wildlife–a pair of toucans, a red and blue macaw, a marmoset, a baby ocelot. How we ended up with the sloth, who seems permanently attached to a sawed-off tree branch, is not clear, but that is because he isn’t very memorable. He simply clings to his branch with a perpetual, near-sighted smile on his face, and ignores everything and everybody.

My mother is in love with all things Ecuadorian, especially the weird things, and she treasures the sloth, along with the guitar made of a (dead) armadillo with his tail still attached, the blow gun, the quiver of curare-tipped darts, and the (fake) shrunken head. The sloth is not interested in her offers of food or drink. She speaks kindly to him, tries to pry him gently away from his branch, all in vain. After several days of total sloth inertia, she concludes that he must be dead. But she is reluctant to part with such an interesting creature, so she decides to have him stuffed and take him back to Spain to amaze the family.

She wraps the sloth in newspaper and hands him to my father to take to the taxidermist. My father puts the dead sloth in the back seat of our 1944 Dodge and stops to do some errands on the way. When he finally arrives at the taxidermist’s and hands him the parcel, the man jumps back. “But the animal is alive!” he exclaims. As my father bends to take a closer look, the formerly dead sloth gives him a lazy wink.

What to do? The animal was dead, and now he is alive–sort of. If he takes him home, will he die again? Softly stroking the sloth’s coarse fur, the taxidermist explains what happened. “He warmed up when you left him in the hot car,” he says. “It’s too cold in Quito for a jungle animal. If you give him to me, I will keep him warm, and he will be happy.” And that is what my father does.

#2–Birmingham, Alabama, 1966. It’s almost the end of the semester, and the last assignment in my Field Zoology class, which until now has focused on fish and birds, is to mount two mammal specimens. I am at a loss as to where to get these specimens until a classmate offers to go squirrel hunting on my behalf. “I can probably get you a chipmunk, too,” he adds.

True to his word, the next day he takes my two specimens, still fresh, out of a bag and plops them on the dissection table. For himself, he says, he will be mounting an opossum. After cutting open the squirrel and the chipmunk and carefully removing the viscera, I stuff them with cotton and sew them closed again. This takes several days, in the course of which my classmate’s dead opossum begins to give off a dead opossum smell. “It’s all that fat on him,” the hunter explains. “He’s a big one.”

My next task is to prepare the squirrel skull by boiling off the meat in a chemical solution. The Field Zoology class ends at noon, and the boiling squirrel skull smells exactly like chicken soup. Between that and the decomposing opossum, a cup of coffee is all the lunch I can manage.

After the final exam, we are free to take our specimens home. I have no use for the squirrel–the sight of it spread-eagled on the mounting board brings back the smell of squirrel soup–but the chipmunk is so cute, all stripes and tiny paws and fluffy tail, that I take him home for my four-year-old sister to play with. She is delighted, but the minute she sets him down, the cat, who has crept unnoticed into the room, pounces on him and carries him off. And that is the last we ever see of the chipmunk.

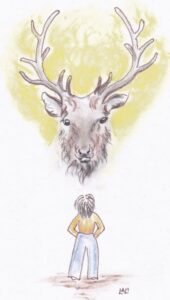

#3 Somewhere in the Tetons, sometime in the 1950s. My husband’s German grandfather shoots an elk, a horse-sized beast with a 12-point rack that fills the family’s freezer to overflowing. Not one to waste anything, Grandpa has the head stuffed. The taxidermist does an excellent job, and the result is both lifelike and the size of a baby-grand piano.

I don’t know where the elk head spends the next quarter century, but in the mid 70s it lands in our house. My husband and I are fresh into our first jobs and in our first house, an elegant brick Georgian which we can afford because it is surrounded by decrepit bungalows in a moribund village in northern Maryland. We don’t have enough money for both a house and furniture, so we are grateful for whatever beds, chests, chairs and random objects are decanted to us from the attics of my husband’s family. And that is how the elk comes to live with us. Our gracefully-proportioned living room has wainscoting and high ceilings with cornices. The fireplace is faced with green marble and yes, there is plenty of room above the mantel for the elk and his rack.

By now, Grandpa’s Elk, by virtue of its age and provenance, has accumulated an almost mystical aura. Everyone remarks how its presence fills the room, but I think the elk would look better in a more rustic dwelling–something in the style of Balmoral perhaps–than in our living room with its pretensions to urban elegance. But I am young and inexperienced, and do not feel entitled to look this gift elk in the mouth.

Over the ensuing years, we move half a dozen times, each time managing to find a spot for Grandpa’s elk. But none of these houses have the character or dimensions to do him justice. In their smaller living rooms he looks like he has accidentally stuck his head through the wall, and the rest of him is out in the yard, waiting to be let in.

When our older daughter moves to her first apartment, I bestow the elk head on her, telling her that it is a way of honoring her adult status. That works for a while, but her next move is to a house that can’t accommodate the elk, so in an unconscious act of lèse majesté, she takes it to an antique store, to be sold on consignment. This decision, when she hears of it, does not sit well with her grandmother, the daughter of the original hunter, who instructs her to retrieve Grandpa’s Elk asap, and generously pays for it to be crated and shipped to a more respectful branch of the family, where, to the best of my knowledge, it is enthroned to this day.

2 Responses

I do not remember this elk from when we visited you. How could I not remember it? Well, there are times when I can’t remember people’s names so I guess that it isn’t surprising that I could forget your elk. Loved reading about it though. I remember the goats.

We stayed up all night talking, then milked the goats at dawn. We must have been very young….